Workshop report

On 27 May 2022, Latin American activists and NGOs, international CSOs and academics gathered in an online workshop to discuss the differential impact on women’s human rights when companies fail to meet their due diligence obligations.

The event was convened by OECD Watch, Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Project (ProDESC), Labour Development Programme (PLADES), Conectas Direitos Humanos (Conectas), and Swedwatch, and was attended by human rights defenders from Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru.

The workshop began with a presentation of OECD Watch’s Guide on Gender Due Diligence, which sets out how civil society can evaluate a company’s due diligence. This was followed by three case studies on harmful impacts of irresponsible business conduct on women; focused on wind farms in Mexico, coffee plantations in Brazil, and the textile industry in Peru. In the first breakout session of the workshop, participants used the guide to identify and assess gaps in the gender due diligence (if any) conducted by companies involved in these cases. After this discussion, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the National Contact Point (NCP) complaint system were explained. In the second breakout session, participants considered whether NCP complaints alleged corporate failures of gender due diligence could and/or should be filed in the three case studies.

This report, also available in pdf in English, Spanish and Portuguese below, provides an overview of the issues and case studies discussed during the online workshop.

How businesses impact women differently

While both men and women may be impacted by corporate activities, both as workers in supply chains and as community members, women experience these impacts differently and often more severely. Women often experience poorer working conditions, low(er) wages, lack of protective clothing or gear, increased land insecurity, and greater health impacts from work-related chemicals and pollution.

There are several factors that worsen impacts on women, including the effects of gender-based discrimination, harrassment, and violence; intersecting identity traits (such as age and ethnicity); conflict settings; risks for women human rights defenders; and cultural barriers such as structural biases against women.

Gender due diligence

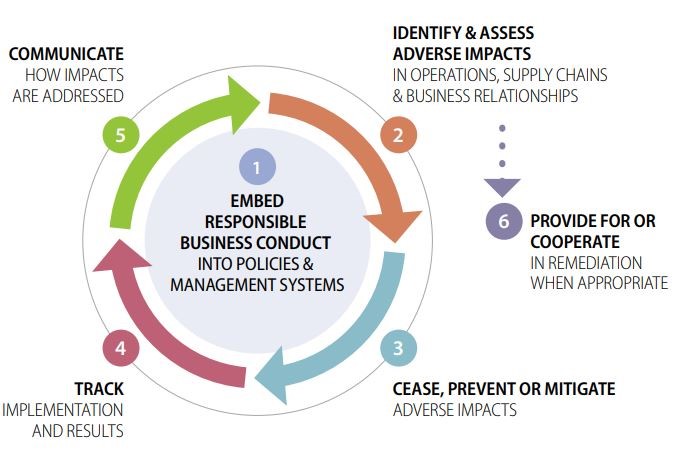

Businesses have a responsibility to anticipate and address their adverse impacts through ‘due diligence’. This responsibility is clearly stated in the two most authoritative instruments on responsible business conduct (RBC) – the OECD Guidelines and the United Nations Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). According to the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for RBC (Guidance):

“Due diligence is the process enterprises should carry out to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for… actual and potential adverse impacts in their own operations, their supply chain and other business relationships.”

According to the OECD Guidance, due diligence should be conducted for all impacts (on human rights, labour rights and the environment, among others), for all sectors and regions, and on both impacts caused by companies and their business partners.

The six steps of due diligence are set out below.

Source: OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, page 21.

Companies are expected to do due diligence with a ‘gender lens’. This means that they should both evaluate, identify, and address risks and impacts to women; and develop gender-sensitive and gender-responsive policies and plans.

OECD Watch’s Guide on Gender Due Diligence

OECD Watch’s Guide to Gender Due Diligence allows CSOs to better understand how companies should conduct gender due diligence. The Guide includes guiding questions to assess whether a company has applied a gender lens at each step of due diligence.

The Guide can be used by CSOs when, for example, interviewing community members, engaging in advocacy towards governments or with companies, and filing complaints.

Case studies on corporate impacts on women

Three case studies on corporate impacts on women were described in the workshop.

Case study: Indigenous women and community members in Unión Hidalgo, Mexico impacted by wind farms

The Mexican organisation ProDESC presented on the impacts of the “Gunaa Sicarú” wind project on women and girls in the Indigenous community of Unión Hidalgo, Mexico. According to ProDESC, French state-owned company Electricité de France and its Mexican subsidiaries and business partners have failed to fulfil their promises to improve the conditions of the local population and adequately mitigate human rights abuses against the general population. They have also exacerbated community violence, particularly affecting women.

While the companies had consulted affected community members, it was highlighted that the lack of an intersectional gender perspective during these consultations affected Indigenous women’s right to free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), as the sessions held to date had not ensured the participation nor representation of women and girls. Only 5% of consultation participants were women, and very few of those women actively participated in the consultations due to fear of attacks. The Mexican government and the companies have thus far made no effort to organise consultation sessions at times and places suitable and accessible to women, nor to provide information in appropriate spaces to encourage the participation of women and girls in the community.

It was also noted that in August 2021, four UN special rapporteurs expressed their concern to the Mexican and French governments, and to the company, to make it clear that appropriate due diligence with a gender lens required companies to identify, prevent and mitigate any human rights impacts generated by the project. Otherwise, these companies may be complicit in violations associated with the wind farm project.

Case study: Coffee workers in Minas Gerais, Brazil

The Brazilian organisation Conectas Direitos Humanos together with rural workers’ advocates exposed the labour rights abuses and modern slavery conditions occurring on coffee plantations in the southern Brazilian state of Minas Gerais.

It was pointed out that multinational companies directly involved in the coffee sector have historically failed to meet their due diligence responsibilities and have arguably contributed to gender inequality and violence in the coffee industry. It was noted that 84.2% of formal workers in the coffee supply chain are men who earn higher incomes than women. Participants also mentioned other gendered impacts, for example, women workers not being allowed to go to the toilet while they work causing health problems, especially during menstruation. Although Brazilian coffee companies claim to have a zero tolerance for slave labour, the compexity of their supply chain (with many intermediaries and no transparency) practically means that abuses against women are relatively commonplace.

Case study: Women textile workers in Peru

The Peruvian organisation PLADES described the negative impacts faced by women workers in the garment industry in Lima, Ica, and Trujillo, Peru. PLADES highlighted precarious health and safety conditions at work, compulsory extended working hours, temporary hiring regimes (including the monthly renewal of work contracts) limiting unionisation, the high degree of labour turnover, and women’s fears that they would be fired if they organise to demand respect for their labour rights.

Many factories in which these women work provide garments to major international companies from many OECD countries. While these companies have codes of conduct and social responsibility policies, there is no evidence that these companies ensure that local production is in compliance with these standards.

The OECD Guidelines’ National Contact Point system

The OECD Guidelines are the leading global standard on Responsible Business Conduct. They are very broad and cover companies and their supply chains, as well as all sectors, all types of multinational enterprises (MNEs), (potentially) all harms occurring in all countries, and all impacts, including on human rights, labour rights, environment, and taxation. They apply to companies causing and contributing to corporate harms or are otherwise found to be directly linked to these harms.

The OECD Guidelines set voluntary standards for companies; however, states are required to establish a complaints mechanism, called a National Contact Point (NCP), to hear and mediate allegations that companies have breached the standards. Complaints can be filed about topics covered by the Guidelines and if the company (or its business partner) is either operating or headquartered in an OECD state.

NCP complaints are generally shorter and cheaper than court cases and can focus on a broad range of issues. Sometimes they have resulted in positive remedy outcomes, such as the adoption of human rights due diligence policies by companies and even substantive remedy outcomes. However, NCPs are entirely voluntary processes and companies are not required to participate in mediation nor comply with any decision or agreement made during the NCP process.

It was pointed out during the workshop that some complaints to NCPs are more likely to be successful, including:

● Complaints filed to more effective NCPs that are willing to investigate claims even if companies do not participate in mediation, make determinations that companies have breached the Guidelines, impose consequences on companies found to be in breach, and consider novel topics or claims.

● Complaints embedded in broader advocacy strategies, including those involving media outreach, parallel complaints, and parallel government, business, or investor advocacy.

● Complaints that seek to influence ‘hard law’ (legislation or case law) through the ‘soft law’ NCP system.

Conclusions and recommendations

The first breakout session in the workshop analysed the three case studies in light of OECD Watch’s gender due diligence guide. Participants considered what steps of gender due diligence the companies did (and did not) take. The second breakout session assessed whether a complaint under the Guidelines was possible and worthwhile for the three case studies. Participants considered whether an NCP complaint could be filed (including whether the impacts and companies were covered by the Guidelines), the goals of impacted women in potentially filing a complaint, and the questions that needed to be answered before deciding to file a complaint.

Based on these discussions, participants identified different challenges to ensuring local and international corporate accountability and access to justice for communities and workers’ collectives in Latin America. Participants outlined recommendations for strengthening the NCP system, including on the justiciability of (or types of claims that can be heard by) NCPs.

Recommendations to the OECD/NCPs:

● There is an absence of clear language on the need for companies to consider intersectional gender perspectives in the OECD Guidelines and associated due diligence documents, as well as amongst NCPs. Some participants suggested that a new chapter on gender be inserted into the Guidelines. Others recommended the adoption of a separate gender due diligence guide by the OECD.

● The gap in access to information remains a challenge for many communities and CSOs, especially in the Global South. This lack of information makes it difficult to engage with complaint mechanisms such as NCPs. Participants encouraged continued capacity building by the OECD and NCPs for different civil society actors as well as encouraging learning and exchange spaces between organisations of different profiles to bridge the knowledge gap, especially in grassroots organisations.

● The OECD/NCPs should conduct additional training on the need for companies to do gender due diligence.

Recommendations to MNEs with responsibilities under the Guidelines:

● There is a general lack of awareness and knowledge by MNEs covered by the Guidelines that they should be conducting due diligence with a gender lens.

● MNEs should increase their awareness and knowledge of gender-related impacts in their supply chains.

● MNEs should also conduct appropriate due diligence as provided in the Guidelines with a gender lens.

Recommendations to civil society:

● CSOs should advocate for increased corporate awareness of gender-related impacts and for businesses to conduct gender-focused human rights due diligence.

● They should also pursue advocacy and complaints against companies for their failures to conduct gender due diligence.

Recommendations to OECD Watch:

● OECD Watch’s gender due diligence guide should be updated to better reflect intersectional issues affecting women.

● OECD Watch should also consider supporting NCP complaints targeting corporate failures to conduct gender-focused due diligence as provided under the Guidelines.