National Contact Point (NCP) complaints can only be filed against companies connected to a harm covered by the OECD Guidelines.

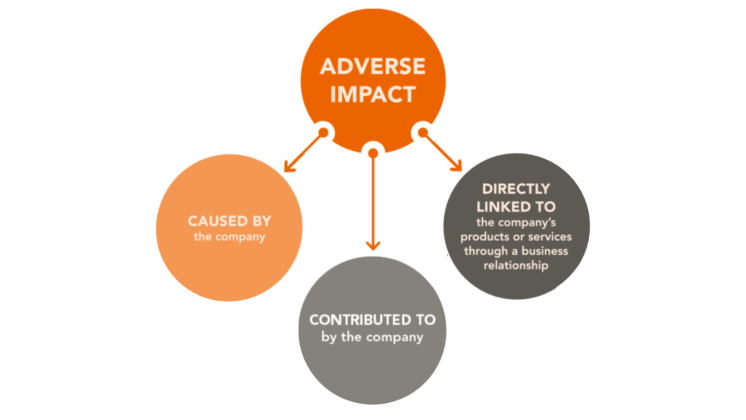

Three levels of company responsibility for harm

There are three ways that a company can be linked to a harm through their activities (including actions or omissions):

- Companies cause a harm where their own activities result in that harm. For example, an employer discriminates against female workers in its hiring practices, or a company pays a bribe to a foreign official.

- Companies contribute to a harm where their activities in combination with other actor(s) cause the harm, or if their activities facilitate another actor to cause the harm. For example, a retailer sets a short delivery time for a product despite knowing from similar products in the past that the production time is not feasible, forcing the manufacturer’s workers to perform excessive overtime. A private investor in a steel plant also sits on the board of the plant, and the investor votes against installing equipment treating run-off from the plant, resulting in the pollution of drinking water of local communities.

- Companies can be directly linked to a harm where there is a link between the harm and their products, services, or operations through business relationships with other actors. For example, an electronics company sources cobalt from a minerals trader that mines using child labour.

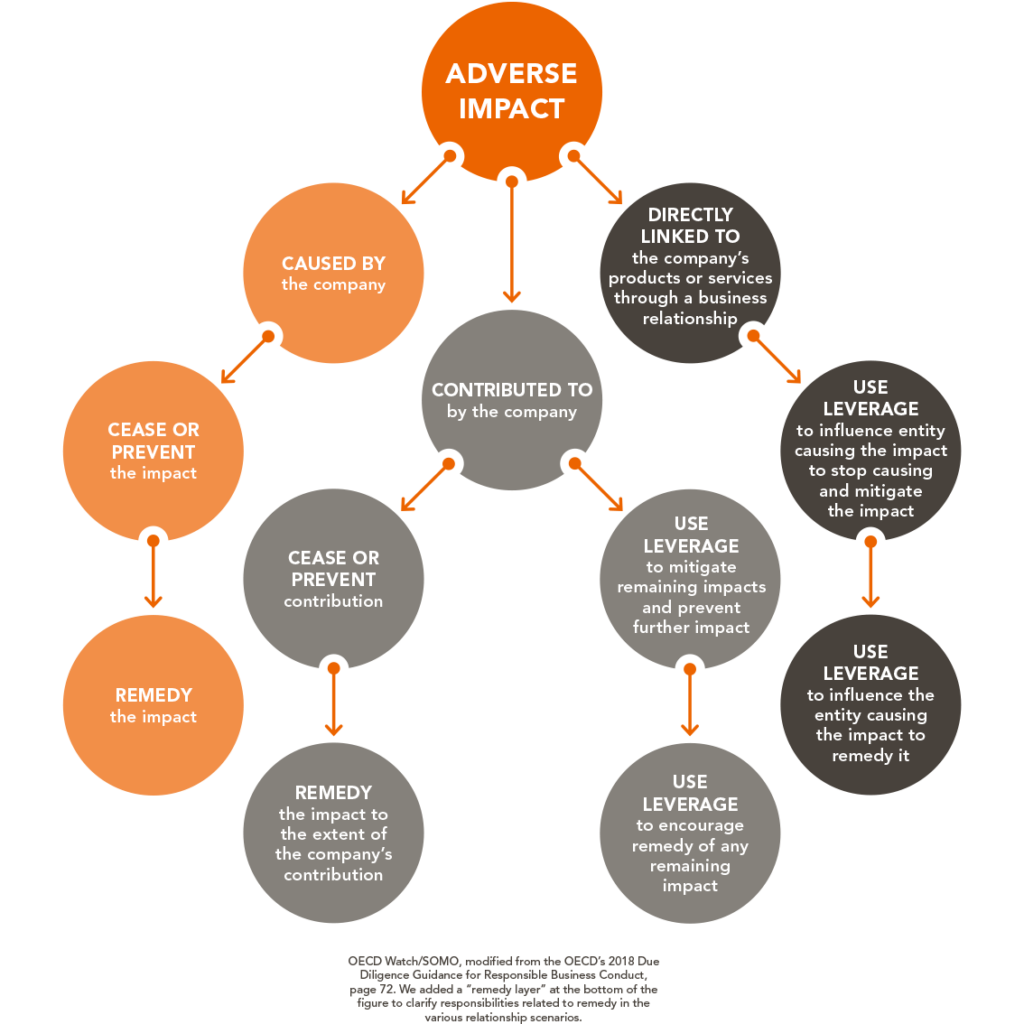

According to the OECD, a company’s relationship to an adverse impact or harm determines the action the company should take to address the harm.

As a general rule, complainants should argue the highest company relationship to harm that is possible and appropriate based on the facts of the case. Contact OECD Watch if you need guidance on this.

Shift in company responsibility for harm

A company’s relationship to harm is not static but can deepen. For example, a company that has only been “directly linked” to harm may later be found to be “contributing” to it. This change depends on a non-exhaustive list of factors, such as whether the company increased the risk of the impact occurring, whether the company knew or should have known about the impacts, and whether the company’s responsive actions actually decreased the likelihood of the impacts (re-)occurring. Other factors may also be relevant, such as how well the company (de-)prioritised addressing the risks or whether its business model is actually exploitative and premised on the risk. Inaction or ineffective action over a long period to mitigate the harm, particularly where a company knows or should have known of the harm, can result in a company shifting from directly linked to contributing. Where relevant, based on the factors present, complainants may wish to argue that a company’s relationship to the harm has deepened.